How We Know What We Know About Milliner Margaret Hunter

How do we know what we know about the past? When we study women and enslaved people, we often have little more than scattered fragments of evidence to work with.

Colonial Williamsburg’s Margaret Hunter Millinery Shop interprets a woman-dominated trade in an original building that was once owned outright by a single businesswoman. But when we study women and enslaved people in the past, we often have little more than scattered fragments of evidence to work with. So how do we really know it was actually owned by Margaret Hunter?

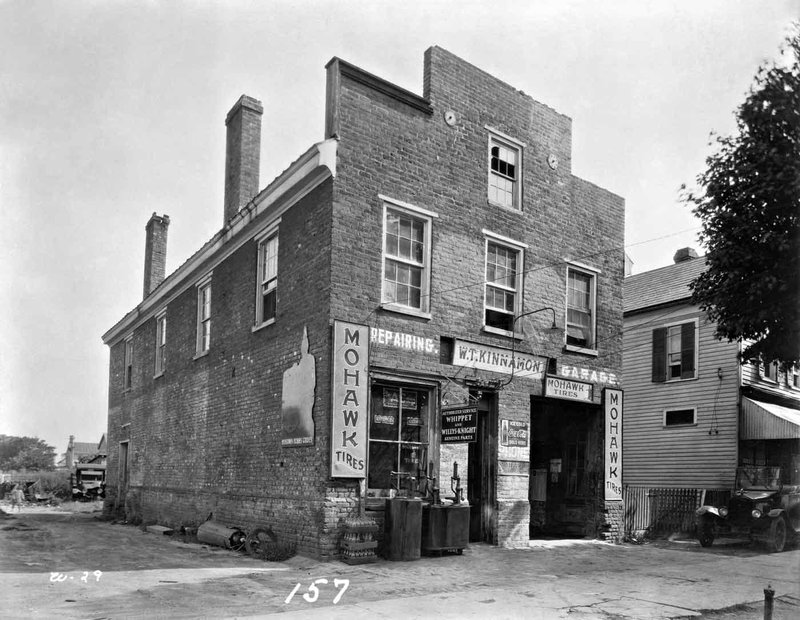

Originally constructed c.1737, the brick building owned by Margaret Hunter from 1774 to 1787 had become Kinnamon’s auto garage when it was purchased by John D. Rockefeller, Jr. as part of Williamsburg’s Restoration. This image documents its appearance in 1926. Photo from the collections of the John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library.

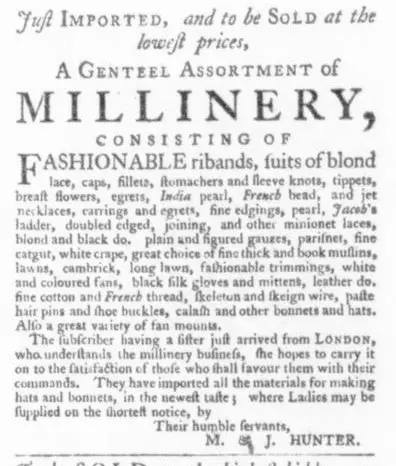

Newspapers are one of the first ports-of-call when looking to research an individual eighteenth-century Williamsburg. The John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library’s large digital collection of Virginia Gazettes is available online, indexed to facilitate browsing for a topic or person. Here we find the first known reference to Margaret Hunter, in an advertisement for a millinery shop she was running with her sister Jane. This describes Margaret a newly arrived from London in the fall of 1767, and notes that she “understands” the millinery business, most likely meaning that she had completed a formal apprenticeship in the trade.

The first evidence of Margaret Hunter in Williamsburg, from an advertisement in Purdie & Dixon’s Virginia Gazette, 1 October 1767.

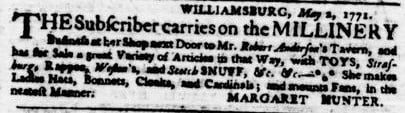

The location of the shop isn’t clear from the advertisement. But we know the sisters continued working side-by-side until Jane went to England temporarily in late 1769, leaving Margaret in charge. No further mention of either of the Hunter ladies appears in the papers until Margaret suddenly began to advertise alone in May 1771, signaling a division of their business.

This apparent rift seems rather puzzling at first, and there are several possible explanations for it. Did Jane die? Did she leave the city? Had there been a disagreement between the sisters? Luckily for us, the Virginia Gazette offers the answer in another advertisement on October 24 of the same year.

Margaret’s first solo advertisement reveals that she relocated to a building “next Door to Mr. Robert Anderson’s Tavern” (now interpreted as Wetherburn’s Tavern). This situation didn’t last long, as a month later, she’s leased “the Corner Store in Doctor Carter’s Brick House” (on the east side of the present-day Golden Ball). It was not until February 5, 1780, that we find “her store opposite to Mr. Ambrose Davenport’s tavern.” No further mention of her location appears in any subsequent advertisement. So how do we know when — or even if — she came to own the specific building we now call “the Margaret Hunter Shop,” on the west side of the Golden Ball?

Margaret Hunter’s first solo advertisement. Virginia Gazette (Purdie & Dixon), 2 May 1771.

While newspapers are an efficient place to start when researching a person from the past, they often aren’t the only primary resource we have available, especially when it comes to tracking individuals known to have owned property. When Richmond burned during the Civil War, nearly all of Virginia’s county records were lost. Fortunately for us, however, Williamsburg straddles two counties, one of which, York County, neglected to send its records to the Confederate capital for “safe keeping.” The York County Project has indexed the court records, tax documents, wills, inventories, and deeds that survive to form this invaluable archive. These records provide the definitive answer to the question of the shop’s location.

A deed for the land on which the present-day millinery shop sits does not survive in the county records. But one for the neighboring lot to the west does. The two properties had once been a single lot which had been subdivided several times prior to Margaret Hunter’s purchase of her quarter lot portion of the land. When William Russell purchased the dwelling to the west of the brick shop on November 15, 1774, the property lines were thus clearly delineated: his land was “bounded . . . on the East by the Lots or parts of lots of James Craig and Margaret Hunter.” Sometime between June 1771 and November 1774, Margaret had purchased the brick building and the land on which it sits, now known as the Margaret Hunter Millinery Shop.

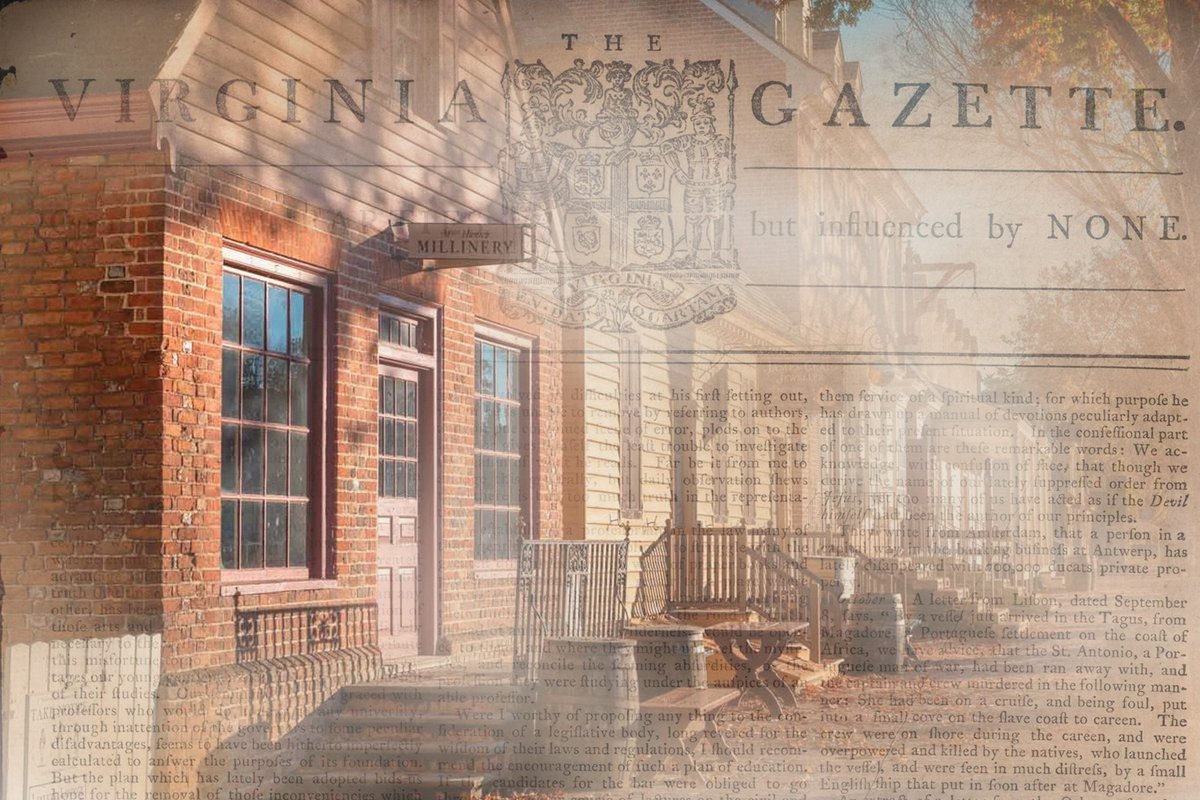

Margaret Hunter leased the section of the building to the right (“the Corner Store in Doctor Carter’s Brick House”) in 1771. By 1774, she had purchased the building on the left, which she owned until her death in 1787. Today, the shop continues to interpret the trade of millinery. Photo from the collections of the John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library.

Margaret remained in possession of the property and continued to operate a shop on site until well after the Revolution. Two issues of the Virginia Gazette alert us to her death on the September 18, 1787: the first simply announces her passing “after a few days illness,” while a second follow-up notice a week later advertises for sale “the property of the late Mrs. Hunter.” This sale, advertised by sister Jane’s husband, Edward Charlton, who was administrator of the will, included “THE BRICK HOUSE . . .situated in the most public part of the city, well calculated for a store or dwelling house, in very good repair, it has a flush cellar, laid with flag stones, and a very convenient kitchen.”

Originally constructed c.1737, the brick building owned by Margaret Hunter from 1774 to 1787 was purchased by John D. Rockefeller, Jr. as part of Williamsburg’s Restoration. Today, the shop has been brought back to its mid-1700s appearance. Photos from the collections of the John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library.

But the county records indicate that the property failed to sell. Another document reveals that Margaret’s land was instead inherited by Jane and the third Hunter sister, Elizabeth Farrow, who still lived in London. On July 14, 1795, Elizabeth sent a formal agreement “to sell to her sister Jane Charlton her half interest in a certain brick dwelling house and premises situate and being in the Main Street of the city of Williamsburg, formerly the property of her late sister Margaret Hunter, spinster, deceased, Jane Charlton and Elizabeth Farrow being joint heirs of Margaret Hunter.”

Jane continued to operate as a milliner until her death in 1802. She likely did so out of the shop she inherited from her sister, continuing a line of savvy businesswomen determined to support themselves in a male-dominated economic system. This is the legacy that the Millinery shop aims to preserve and to share daily, as modern-day milliners continuing the practice of a traditionally feminine trade in a shop that did the same 250 years ago.

Resources

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), 20 June 1771.

- York County Records, Deeds, Book VIII, p. 461.

- Virginia Gazette (Nicolson), 4 October 1787.

- Ibid., 11 October 1787.

- York County Records, Deeds, Book VII, p. 171.