Who Was Logan? The Mystery at the Heart of the Shawnee-Dunmore War

In his time, Logan was one of the most famous Indigenous people in North America. Today, we’re not certain what his full name was.

Logan was a leader among the Mingo people, who were ancestors of today’s Seneca-Cayuga Nation.1 He and his family had long helped to maintain peaceful relations between white colonists and American Indian nations in the Ohio Valley. But after white settlers killed many of his family members in 1774, Logan struck back with a series of raids that helped to spark the Shawnee-Dunmore War. Logan documented his perspective on the murder of his family members and the war in a famous oration known as “Logan’s Lament.”

But what about Logan’s background? We know that he was the son of an Oneida leader named Shickellamy. But Shickellamy had two sons named Logan, both named after a Pennsylvania government administrator he had worked with, called James Logan. At this time, some Native people used two names, one for settlers, and one among their own people. Shickellamy’s eldest son Tachnedorus (meaning “spreading oak”) was called John Logan, while his second son Soyechtowa was known as James Logan.2

So who was Logan? Let’s explore the evidence.

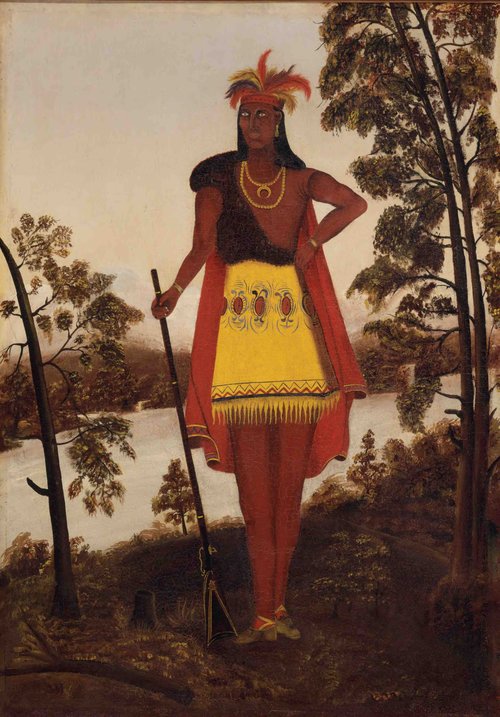

“Portrait of the Oneida Chieftain Shikellamy,” (ca. 1820). Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

“Logan is the friend of White men”: Diplomacy

At a time of growing violence between Native people and British colonists, Logan and his family helped to ease tensions.3 In his “Lament,” Logan recalled that he was a “friend of White men,” someone who urged his friends and neighbors to refrain from violence and co-exist with British settlers.4 He was known for his “love for the Whites,” so much so “that those of my own Country pointed at me as they passed by and said Logan is the friend of White men.”5

Indeed, Logan explained he had gone out of his way to accommodate white settlers. He called for “any White man to say if ever he entered Logan’s Cabin hungry and I gave him not meat, if ever he came cold or naked and I gave him not Cloathing.” This passage of the “Lament” bears a striking similarity to a passage from the Christian Bible. The Book of Matthew, chapter 25, reads, “For I was an hungred, and ye gave me meat: I was thirsty, and ye gave me drink: I was a stranger, and ye took me in.”6 Logan may have read the Bible. One settler later claimed that John Logan (Tachnedorus) had told him that many Native people “can read the Buck [book] that speaks of God.”7 Logan, or perhaps some members of his family, may have been able to read English. This was a valuable skill for someone who frequently moved between settler and Native cultures.

“This called on me for revenge”: The Yellow Creek Massacre

Logan’s friendships with white settlers did not protect his family. In the 1760s and 1770s, the Ohio Valley witnessed an escalating series of violent confrontations between colonists and Indigenous people. On April 30, 1774, a group of white settlers led by Jacob and Daniel Greathouse murdered much of Logan’s family at a settlement near the upper Ohio River. While the precise details are disputed, it appears that the white party ambushed Logan’s family in a tavern, killing eight people. These included Logan’s brother John Petty, his mother Neanoma, his sister Koonay, and her young child.8

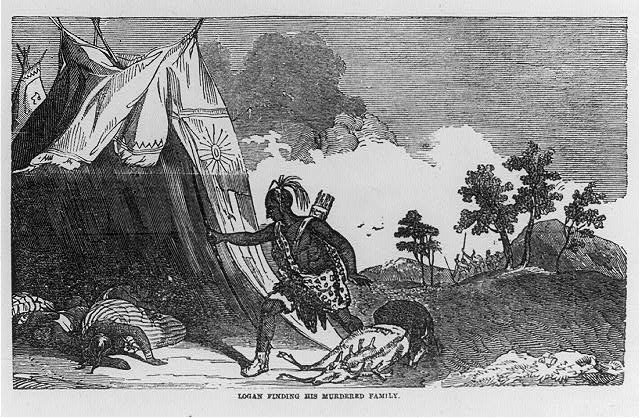

“Logan Finding His Murdered Family,” from John Frost, Pictorial History of Indian Wars and Captivities (New York: Wells Publishing Company, 1873).

Logan blamed the attack on a notorious frontier colonist named Michael Cresap. This was a reasonable assumption, given Cresap’s violent reputation. Yet Cresap was probably not directly involved in the Yellow Creek Massacre.9 Nevertheless, Logan raised a war party that sought vengeance by attacking several white settlements, including one near Cresap’s home. Virginians responded by raising a militia that marched west, leading to the Shawnee-Dunmore War. The Virginia militia confronted a coalition of Shawnee, Mingo, Wyandot, and Delaware warriors. After the militia won the Battle of Point Pleasant, the parties agreed to peace.10

The Shawnee-Dunmore War

How did a coalition of Shawnee, Mingo, and other Native people come together to challenge British colonists’ seizure of their land?

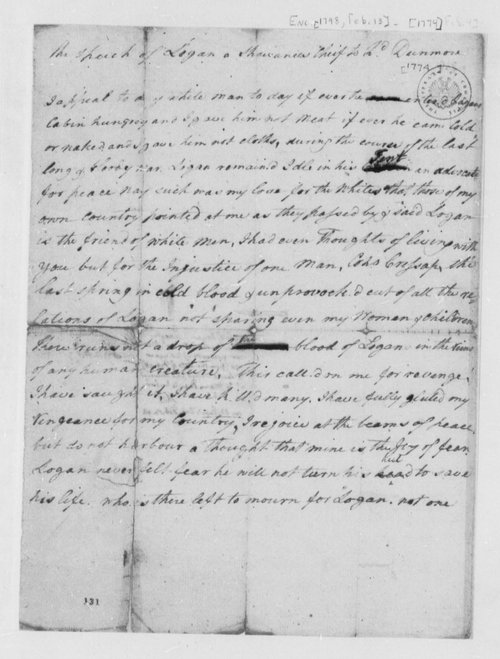

Thomas Jefferson’s manuscript version of Logan’s Lament. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

“Who is there to mourn for Logan?”: Logan’s Lament

Logan did not participate in peace negotiations. But he met his brother-in-law John Gibson, who was the husband to Logan’s murdered sister Koonay. The Virginians had sent Gibson as an envoy. Gibson later recalled that Logan led him out “into a Copse of Woods,” where he wept and delivered his famous speech. Gibson relayed the speech to Lord Dunmore, Virginia’s governor.11

It quickly spread. Thomas Jefferson recalled that Dunmore’s party returned with a copy of Logan’s Lament, which circulated through Williamsburg. Jefferson later wrote that the speech was “so fine a morsel of eloquence that it became the theme of every conversation, in Williamsburg particularly.” The first documented version of Logan’s Lament appears in a letter that James Madison wrote to a Philadelphia printer (whose newspaper was the first to publish it). That version follows:

I appeal to any White man to [say] if ever he entered Logan’s Cabin hungry and I gave him not meat, if ever he came cold or naked and I gave him not Cloathing. During the Course of the last long and bloody War, Logan remained Idle in his Tent an Advocate for Peace; Nay such was my love for the Whites, that those of my own Country pointed at me as they passed by and said Logan is the friend of White men: I had even thought to live with you but for the Injuries of one man: Col. Cresop [Michael Cresap], the last Spring in cold blood and unprovoked cut off all the Relations of Logan not sparing even my Women and Children. There runs not a drop of my blood in the Veins of any human Creature. This called on me for Revenge: I have sought it. I have killed many. I have fully glutted my Vengeance. For my Country I rejoice at the Beams of Peace: But do not harbour a thought that mine is the Joy of fear: Logan never felt fear: He will not turn his Heal to save his life. Who is there to mourn for Logan? Not one.

“Logan’s Lament,” as this speech became known, was widely praised for its elegance of expression. Jefferson republished it in his 1781 book Notes on the State of Virginia. It appeared regularly in magazines and newspapers in the early nineteenth century. Many schoolchildren memorized the “Lament.” One mid-nineteenth-century magazine editor claimed that Logan’s speech did more than any other “to form the mind and develop the latent energies of the youthful American orator.”12 Logan became a mythical figure, known to millions of Americans.

Yet little is known about Logan’s life after this event. According to the Moravian missionary John Heckewelder, Native people spoke of Logan’s “deep Melancholy.” Rumors spread that he had become suicidal. He died around 1780.13

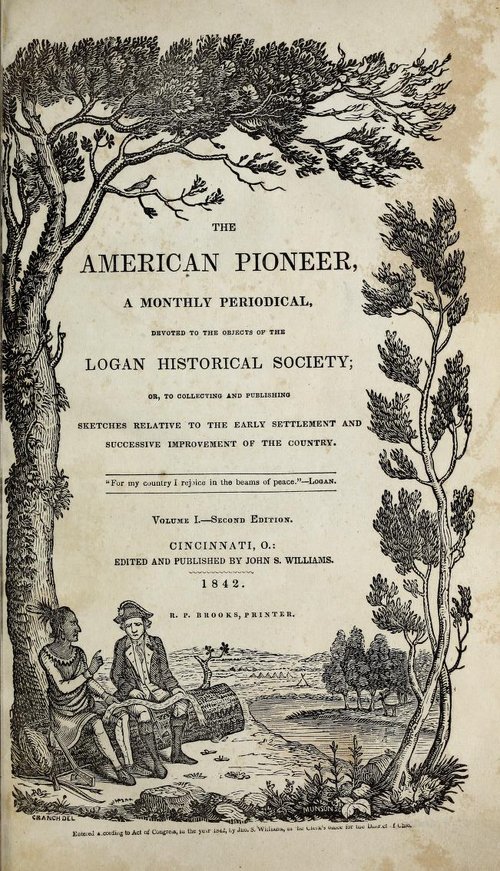

The cover page for the first issue of The American Pioneer, a publication of the Logan Historical Society, featured an image of Logan and John Gibson speaking under a tree.

The Mystery of Logan’s Identity

Who was Logan the orator? He was a man of peace, pulled by murder into war. He was eloquent and thoughtful. He was influential. He was famous. Yet it remains unclear which son of Shickellamy was the famous Logan. Was it the eldest son Tachnedorus (John Logan) or the second son Soyechtowa (James Logan)? Historians are divided.14

Some evidence points to Tachnedorus. Most compelling is a letter that Logan dictated for Michael Cresap in 1774. It was signed “Captain John Logan,” which suggests that Logan was Tachnedorus.15 But other accounts suggest that Logan the orator was Soyechtowa. Heckewelder clearly identified Logan as “the second son of Shikellemus.”16 Likewise, a 1915 family history given by a 106-year-old Jesse Logan, a grandson of Tachnedorus, indicates that “the immortal Cayuga orator” was his great-uncle Soyechtowa.17

These sources are each imperfect. We may never definitively know the answer.

But it is no mystery why the identity of the famous Logan remains obscure. Written records generally reflect the interests and perspectives of colonists, rather than Indigenous people. Almost everything we know about Logan, his family, his raids, his “Lament,” and his death, comes to us through colonists’ hands.18 For that reason, Logan’s specific identity is likely to remain enigmatic for generations to come.

Sources

Cover image: S. G. Goodrich, Johnson’s Natural History, vol. 1 (New York: 1881), p. 53.

- Logan has been variously identified as Mingo, Cayuga, and Haudenosaunee (or Iroquois). His mother was Cayuga while his father was from the Oneida nation, which were among the Six Nations of the Haudenosaunee or Iroquois Confederacy. Since Haudenosaunee society was matrilineal, meaning that family identity descended through the mother, Logan was probably considered a Cayuga person at birth. But by his adulthood, Logan seems to have identified with the Mingo people, a term which refers to Iroquoian-speakers in the Ohio Valley. Today, the term “Mingo” is often considered derogatory, since it was derived from an Algonquian word meaning “sneaky.” Robert Parkinson, Heart of American Darkness: Bewilderment and Horror on the Early Frontier (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2024), 66.

- Parkinson, Heart of American Darkness, appendix.

- Parkinson, Heart of American Darkness, 92-94.

- As discussed below, the earliest known written version of Logan’s Lament appears in a letter from James Madison to William Bradford, printer of the Pennsylvania Journal. “From James Madison to William Bradford, 20 January 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-01-02-0039.

- “From James Madison to William Bradford, 20 January 1775.”

- This comes from the King James translation of the Bible, which was widely used in the British colonies during the eighteenth century. See Matthew 25:35, The Holy Bible, Containing The Old Testament, and The New (T. Weight and W. Gill, 1774).

- Archibald Loudon, A Selection of Narratives of Outrages Committed by the Indians in Their Wars with the White People (New York: Garland Publishing, 1977), vol. 2, 225, link.

- Parkinson, Heart of American Darkness, 179–181.

- Parkinson, Heart of American Darkness, 198, 202-5.

- Colin G. Calloway, The Shawnees and the War for America (Penguin: 2008), 55–57.

- “To Thomas Jefferson from John Gibson, 17 June 1797,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-29-02-0346.

- Carolyn Eastman, “The Indian Censures the White Man: ‘Indian Eloquence’ and American Reading Audiences in the Early Republic,” William and Mary Quarterly 65 (July 2008): 540.

- One contemporary source claims that Logan’s nephew killed him. See Donald H. Kent and Merle H. Deardorff, “John Adlum on the Allegheny: Memoirs for the Year 1794: Part II,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 84 (Oct. 1960, no. 4): 471–72.

- An excellent overview of scholarly debates of Logan’s identity appears in Parkinson, Heart of American Darkness, appendix.

- Reuben Gold Thwaites and Louise Phelps Kellogg, eds., Documentary History of Dunmore’s War (Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 1905), 247, link.

- Heckewelder wrote his recollections of Logan for inclusion in an appendix of a later edition of Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia, after some disputed Logan’s authorship of the “Lament.” Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia (Lilly & Wait, 1832), 265, link.

- Henry W. Shoemaker, Captain Logan, Blair County's Indian chief; a biography (Altoona Tribune Publishing Company, 1915), 38–40.

- Parkinson, Heart of American Darkness, 383.