John Murray, Fourth Earl of Dunmore

On This page

Before Virginia

Sir Joshua Reynolds, “John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore,” 1765, National Galleries of Scotland .

“Damn Virginia—Did I ever seek it? Why is it forced upon me?”1 John Murray, Fourth Earl of Dunmore, did not want to go to Virginia.2 For many royal officials, Virginia would have been a plum job. But for Dunmore, it was a poisoned chalice. As Virginia’s governor, he would be embroiled in constant controversy and conflict. A simmering revolution would come to a full boil under his watch.

Scottish-born Lord Dunmore had arrived in New York in 1770 to become the colony’s royal governor. He came alone, leaving his wife Charlotte and eight children in Britain. Despite navigating the many quarrels in New York politics and gaining a reputation as “a gamester . . .and a Drunkard,” Dunmore liked it there.3 After less than a year, the British administration reassigned him to Virginia. Dunmore resisted the move, complaining that Virginia had a poor climate and “little or no society.”4 After months of grumbling and delaying, he grudgingly trekked south. He arrived in Williamsburg, Virginia’s capital, in 1771.5 His reputation preceded him.

Controversy

Dunmore quickly embroiled himself in local scandal. He allegedly had an affair with Kitty Eustace Blair, who was battling her estranged husband in court. Dunmore was chief justice in the case. Ugly, and likely untrue, rumors also surfaced about a suspected relationship with Sukey Randolph, the attorney general’s daughter.6

Despite rising political tension, Dunmore forged relationships with prominent members of Virginia’s social circle. On June 24, 1774, George Washington recorded an outing with Dunmore, “Rid out with the Govr. to his Farm [Porto Bello] and Breakfasted with him there.”7 Later that same day, Dunmore asserted his royal power by dissolving the House of Burgesses, including George Washington, to prevent them from formally protesting British policies. The former burgesses defied the governor by meeting the next day at the Raleigh Tavern and agreeing to a boycott of British goods.8

Earlier in 1774, Dunmore’s wife and six of their children had arrived in Williamsburg after being apart for three years.9 Ten months after Lady Dunmore’s arrival, the Dunmores welcomed their ninth child, a daughter they named Virginia. Murray missed her birth by a day.10 He had been trekking back to Williamsburg from the frontier, where he led Virginia’s militia in a war against a coalition of Indigenous nations, including the Shawnee. The Virginians emerged victorious in the Shawnee-Dunmore War, and the Shawnee and their allies signed a treaty ceding land to Virginia.11 Dunmore returned to Williamsburg more popular in Virginia than he had ever been. It did not last long.

The Shawnee Dunmore War

Learn more about the Shawnee-Dunmore War, the war Dunmore waged against allied Shawnee and Mingo people in the Ohio River Valley.

Revolution brewed in Williamsburg, and Dunmore was helpless to stop it. In April of 1775, he followed orders from London to remove gunpower from the public Magazine. News of the action sparked outrage among Virginians, who threatened to march on the city. Dunmore, preparing for the worst, sent his family out of the city and turned the Governor’s Palace into a fortress. “The Commotion in this Colony . . . has obliged me to shut myself in and make a Garrison of my House expecting every Moment to be attacked,” he wrote.12 The controversy ended without bloodshed, but it undermined Dunmore’s authority. Within two months, he left the Governor’s Palace for what would be the last time.

Dunmore’s Proclamation

Dunmore’s position was weak, but he did not leave Virginia. He fled to a ship in the York River, hoping that the British army would be able to stop the rebellion.

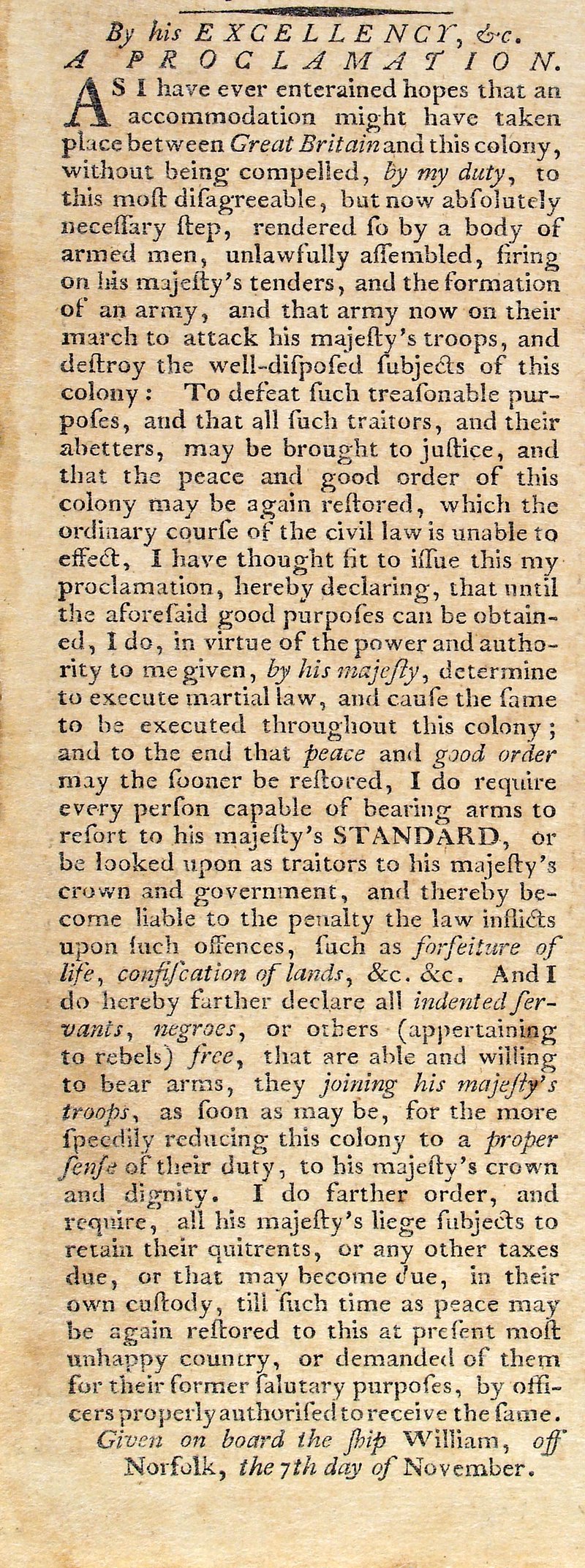

In November of 1775, Dunmore released a proclamation that would define how we remember him today. Dunmore’s Proclamation declared martial law and took the extraordinary step of freeing all indentured servants and enslaved people belonging to rebels who were “able and willing to bear arms,” when they joined “his majesty’s troops.”13

Virginia Gazette (Purdie), November 24, 1775.

Virginia’s Patriots found the proclamation to be “fatal to the publick Safety” and called it a “cruel policy.”14 George Washington called Dunmore an “Arch Traitor to the Rights of Humanity.”15 They responded by increasing patrols and creating policies to punish self-emancipated people. Even so, hundreds answered the call and set out to join Dunmore’s forces.16 About three hundred served in Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment, seeing action in the Battle of Great Bridge.17

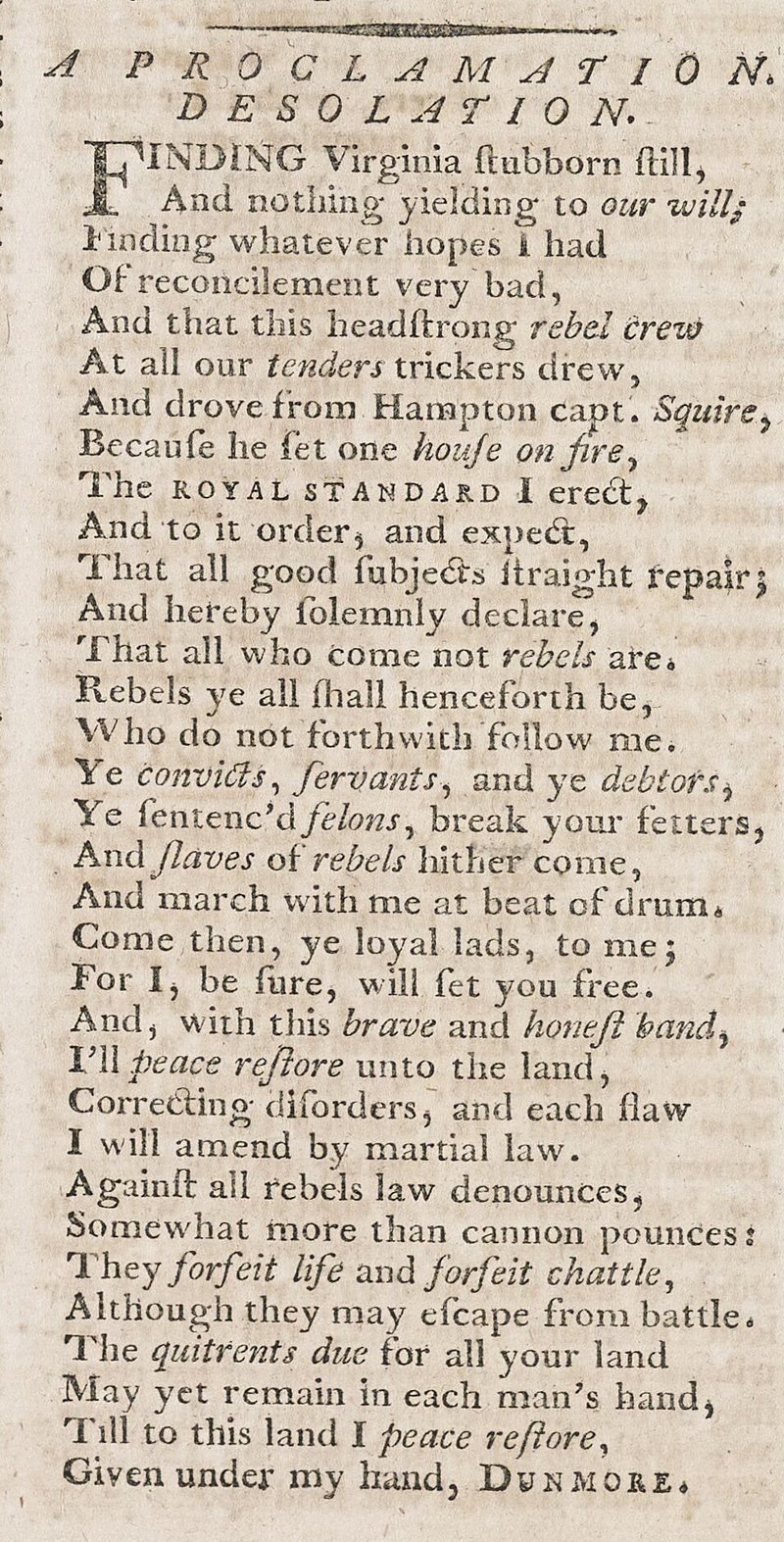

“A Proclamation Desolation,” Virginia Gazette (Purdie), December 8, 1775.

Legacies

After the Revolution, Dunmore added a pineapple to a 1761 building on his property in Scotland. The Pineapple, Karen Howie, Wikimedia Commons, shared under a CC by S-A 4.0 license

Dunmore remained in Virginia as long as he could, but by 1776 it was clear that he was not going to retake Virginia. He left, but remained engaged in the war effort.18 After the war, he supported Loyalists in London who petitioned the Crown to compensate their losses. He continued to work with Loyalists when he was appointed governor of the Bahamas, which had seen a large influx of white and Black Loyalists after the war.

Dunmore fell from favor after his daughter Augusta became embroiled in a controversy of her own. She married the King’s son, Prince Augustus Frederick Hanover, without first getting permission from his family.19 Dunmore was recalled from the Bahamas under accusation of corruption.20 He lived in Kent, England until his death in 1809.21

Was Dunmore a savvy politician who simply could not stem the tide of change? Or was he a bumbling opportunist who bungled his job so badly it helped usher in a revolution? Was he an advocate for freedom? Or a pragmatist using the tools at his disposal to force revolutionaries’ hands? Dunmore’s story is more complex than any single depiction. He didn’t seek out Virginia, but he left a complicated legacy of freedom behind him. After Dunmore, Virginia was permanently transformed.

Miniature Portrait of John Murray, Fourth Earl of Dunmore (ca. 1809-1830), Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. 2003-58

Sources

- William H.W. Sabine, ed., Historical Memoirs from March 16, 1763 to July 9, 1776, of William Smith, vol. 1 (New York Times & Arno Press, 1956), 107. The full quote, which Chief Justice William Smith recorded in his diary that Dunmore “was heard to say,” is “Damn Virginia—Did I ever seek it? Why is it forced upon me? I ask’d for New York—New York I took, & they have robbd me of it without my Consent.”

- James Corbett David, Dunmore’s New World: The Extraordinary Life of a Royal Governor in Revolutionary America—with Jacobites, Counterfeiters, Land Schemes, Shipwrecks, Scalping, Indian Politics, Runaway Slaves, and Two Illegal Royal Weddings (University of Virginia Press, 2013), 41–42.

- William Aitchison to Charles Steuart, October 17, 1770, Charles Steuart Papers, quoted in David, Dunmore’s New World, 43.

- Earl of Dunmore to the Earl of Hillsborough, July 2, 1771, CO 5/54, National Archives, London.

- David, Dunmore’s New World, 26–42.

- David, Dunmore’s New World, 51; Frank L. Dewey, “Thomas Jefferson and a Williamsburg Scandal: The Case of Blair v. Blair,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 89, no. 1 (January 1981): 44–63; James Parker to Charles Steuart, November 18, 1772, Charles Steuart Papers, National Library of Scotland. James Parker to Charles Steuart, May 19, 1773, Charles Steuart Papers, National Library of Scotland. In July of 1774, after Lady Dunmore joined Dunmore in Virginia, Augustine Prevost wrote in his diary that “His Lordship is I believe a consummate rake.” Nicholas B. Wainwright, “Turmoil at Pittsburg: Diary of Augustine Prevost, 1774,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 85, no. 2 (April, 1961), 123.

- “[Diary entry: 26 May 1774],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/01-03-02-0004-0009-0026. George Washington noted socializing with Lord Dunmore before this as well: for example, he wrote in his diary on October 31, 1771, “Dined at the Governors & went to the Play.” “[Diary entry: 31 October 1771],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/01-03-02-0001-0025-0031.

- John Pendleton Kennedy, ed., Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia 1773-1776 including the records of the Committee of Correspondence (E. Waddey Co., 1905), 132; Lord Dunmore to Lord Dartmouth, May 5-29, 1774, CO 5/1352, National Archives London, UK; “An Association, signed by 89 of members of the Late House of burgesses,” May 27, 1774, https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/DigitalLibrary/view/index.cfm?doc=Manuscripts%5CM19292.xml&.

- David, Dunmore’s New World, 52.

- David, Dunmore’s New World, 56.

- David, Dunmore’s New World, 56-93. For more on the Shawnee-Dunmore War, often called Dunmore’s War, see: Rueben Gold Thwaites and Louise Phelps Kellogg, eds., Documentary History of Dunmore’s War (Wisconsin Historical Society, 1905), 93; Robert G. Parkinson, Heart of American Darkness: Bewilderment and Horror on the Early Frontier (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2024); Glenn F. Williams, Dunmore’s War: The Last Conflict of America’s Colonial Era (Westholme Publishing, 2017).

- Earl of Dunmore, May 15, 1775, CO 5/1373, National Archives London.

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie), November 24, 1775, link.

- Patrick Henry to Committee of Safety, November 20, 1775, https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/rbc/rbpe/rbpe17/rbpe178/1780180a/1780180a.pdf. Virginia Gazette (Pinkney), Nov 30, 1775, 3, link.

- “From George Washington to Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Reed, 15 December 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0508.

- Benjamin Quarles, “Lord Dunmore as Liberator,” William and Mary Quarterly 15, no. 4 (Oct. 1958): 498–500, 506. Quarles estimated that “perhaps not more than a total of eight hundred slaves had succeeded in reaching the British” by July of 1776.

- Quarles, “Lord Dunmore as Liberator,” 503.

- David, Dunmore’s New World, 125–28.

- David, Dunmore’s New World, 172.

- David, Dunmore’s New World, 175.

- David, Dunmore’s New World, 181–83.