George Mason

A “forgotten founder,” George Mason was an influential planter, statesman, and thinker who inspired the colonies to boycott British goods and later authored the Virginia Declaration of Rights, which served as a model for the Bill of Rights.

On This page

Stirring the Revolutionary Pot

George Mason (1725–1792) had little formal education, but he developed a deep interest in Enlightenment thought. He followed in his father’s footsteps when he was elected to Virginia’s House of Burgesses in 1759. Mason opposed the British policies that would lead to revolution and was active in local committees of safety and correspondence. In 1774 Mason drafted the Fairfax Resolves, which paved the way to the Continental Association, bringing the colonies together in a boycott of imported British goods.

During the American Revolution, Mason served in the House of Burgesses and Patriot committees in his home county of Fairfax, where he was a neighbor of George Washington. He was frequently absent due to illness, which contributed to his resignation from the committee assigned to revising Virginia’s laws after independence.

We came equals into this world, and equals we shall go out of it.

— George Mason

His Greatest Contribution

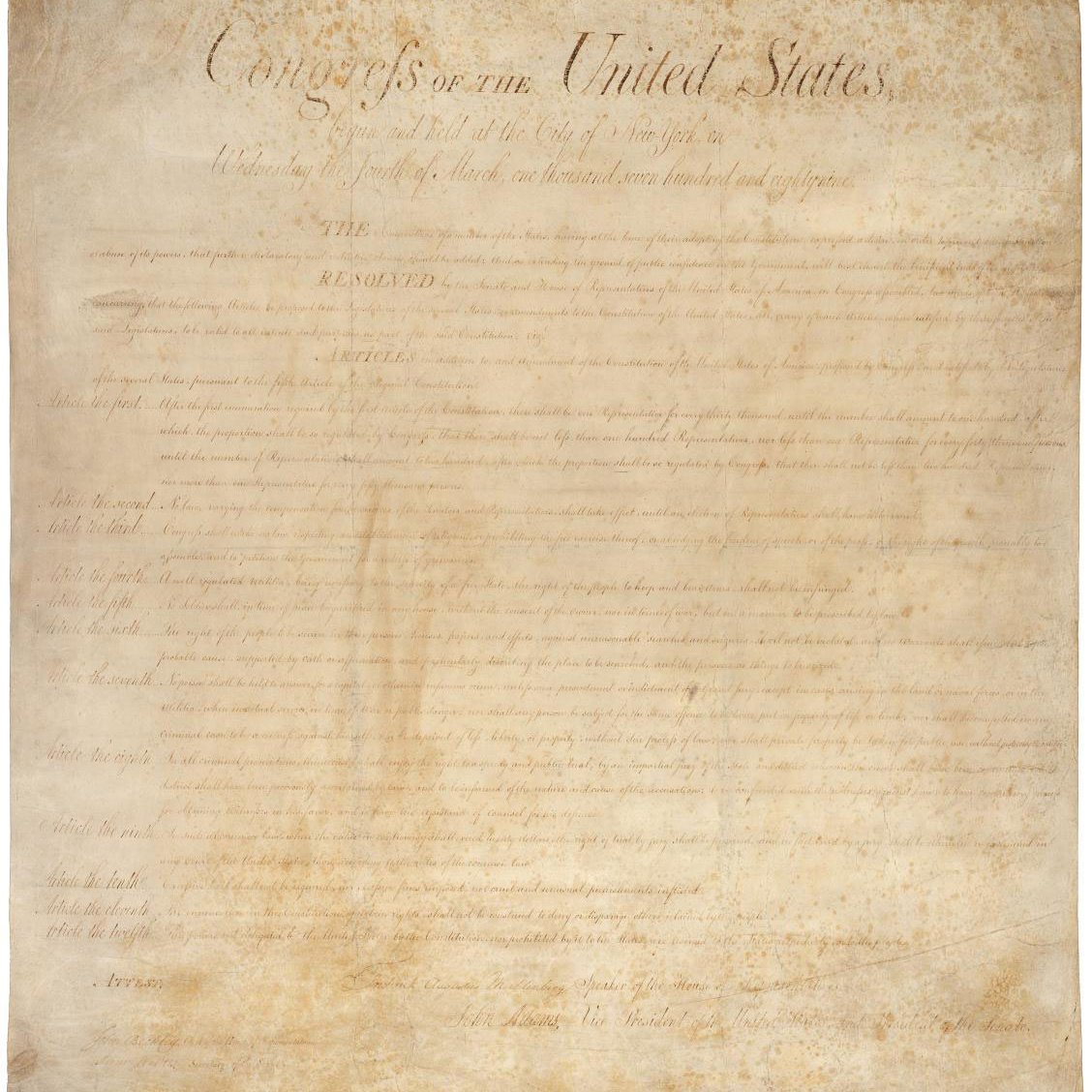

On June 12, 1776, the Fifth Virginia Convention adopted Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights in Williamsburg’s Capitol. The principles listed in this document were not new, but the idea that government derived its power from the people gave it new authority. The document included freedom of the press and religion, the right to trial by jury, and civilian control of the military. It also proclaimed that “all men are by nature equally free and independent and have certain inherent rights [including] life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness.” The document served as the basis for the U.S. Bill of Rights and a model for enshrining individual liberties into law.

Rights, Above All

A decade after independence, Mason was a vocal participant in debates at the Constitutional Convention in 1787. But he refused to sign the finished Constitution because it failed to include a bill of rights. He worried that the new government might descend into “a corrupt, tyrannical aristocracy.”

Despite his political achievements, he preferred family life at Gunston Hall, his plantation home near the Potomac River. He had nine children who survived to adulthood with his first wife, Ann Eilbeck, who died in 1773. He remarried in 1780. At the end of the Revolution his property holdings included ownership of more than 5,000 acres of land near the Potomac River and 128 enslaved African Americans.

Resources

- The Papers of George Mason; Volume I-III, edited by Robert A. Rutland (Kingsport: Kingsport Press, 1970)

- Pamela C. Copeland & Richard K. MacMaster The Five George Masons: Patriots and Planters of Virginia and Maryland, (Fairfax, VA, George Mason University Press) 2016

- Jeff Broadwater George Mason: Forgotten Founder (Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Press) 2006